30 The premortem

The premortem is a project management technique designed to identify risks before project execution begins. Unlike a postmortem, which analyses failures after they’ve occurred, a premortem works on the assumption that a project has already “failed” and asks team members to generate plausible reasons for this hypothetical failure. This “prospective hindsight” approach enables teams to identify potential problems early and modify plans accordingly. Klein (2007) writes, “a premortem may be the best way to circumvent any need for a painful postmortem.”

30.1 Evidence

The academic literature on the premortem is thin.

The sole citation in Klein (2007) relates to research by Mitchell et al. (1989), who demonstrated that imagining that an event has already occurred with certainty, rather than considering that it may occur, increases the number of reasons generated for the potential future outcome by approximately 30%. Mitchell, Russo, and Pennington (1989) did not assess the quality of the reasons.

(Note the difference between what I have written in this sentence and how Klein (2007) references this paper: “Research conducted in 1989 by Deborah J. Mitchell, of the Wharton School; Jay Russo, of Cornell; and Nancy Pennington, of the University of Colorado, found that prospective hindsight—imagining that an event has already occurred—increases the ability to correctly identify reasons for future outcomes by 30%.”)

Veinott et al. (2010) evaluated the premortem technique against other plan evaluation methods. 178 university students assessed an H1N1 lockdown plan under five conditions. The results showed that imagining a plan has already failed reduced confidence significantly more than the other approaches—about twice the effect of Pro/Cons or Cons-only methods. After generating solutions, confidence increased most in the PreMortem condition. The researchers attribute the premortem’s effectiveness in reducing confidence to two mechanisms: the certainty frame (assuming failure has occurred) and the focus on failure reasons, concluding it is a valuable tool for crisis management planning.

Gallop and Bischoff (2016) conducted a controlled study comparing brainstorming and premortem techniques for risk identification. Using 101 experienced program managers and engineers, they found that teams using the premortem technique identified significantly more “quality risks” (both creative and plausible) and developed more effective changes to project plans than teams using traditional brainstorming. Importantly, premortem teams were more successful at identifying “black swan” risks—hard-to-predict, potentially catastrophic events that were missed in the historical case their scenario was based on. The researchers attributed this success to the premortem’s ability to neutralise “deliberate ignorance” and facilitate differing perspectives within teams, creating more robust risk identification.

30.1.1 The experimental methodology

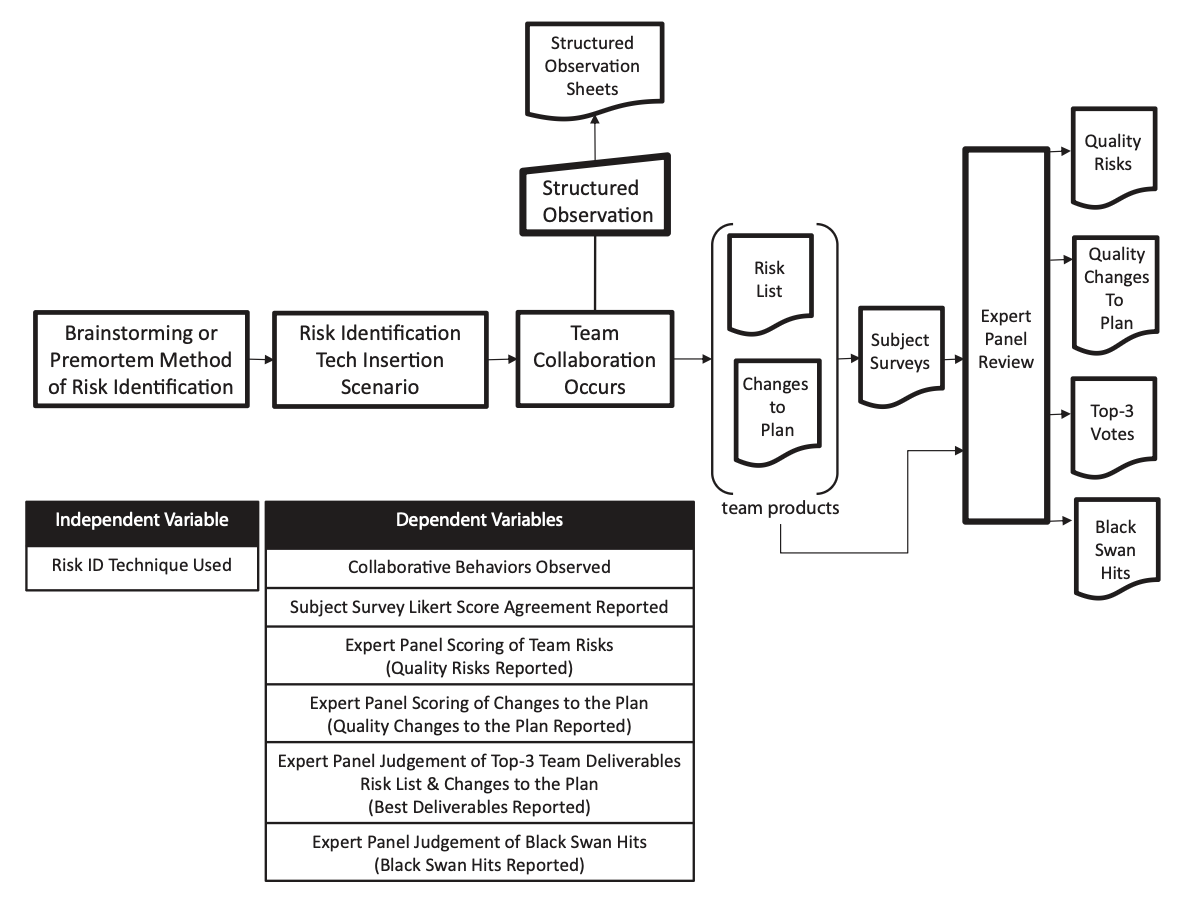

The participants in the Gallop and Bischoff (2016) experiment were randomly assigned to teams of 4-6 people. Each team was trained in either brainstorming or premortem techniques before being presented with an identical technology insertion scenario—adding a proximity fuse to a torpedo previously using only a contact fuse. Teams were given 45 minutes to identify risks and recommend changes to the plan.

Structured observation was used to measure collaborative behaviours during the sessions, tracking four specific interactions: generation of unique risk ideas, enrichment of others’ ideas, offering different perspectives, and critique of ideas. Following each session, participants completed surveys using a six-point Likert scale to assess their perception of team collaboration and technique effectiveness. This dual approach allowed researchers to compare observed behaviours with participants’ subjective experiences.

An expert panel of senior faculty members independently evaluated each team’s deliverables. They scored risks on creativity and plausibility, and changes to the plan on creativity and usefulness, with scores above 70 in both dimensions qualifying as “quality” outputs. The panel also identified which team-generated risks matched the actual “black swan” risks from the historical case the scenario was based on. This blind review process ensured unbiased assessment of output quality and effectiveness across the two techniques.

30.2 The premortem process

According to Klein (2007), a typical premortem follows this structure:

- Initial briefing: The team is first briefed on the project plan.

- Hypothetical failure: The leader informs everyone that the project has failed spectacularly.

- Independent reflection: Team members individually write down every possible reason for the failure, particularly issues they might not normally mention out of politeness or political concerns.

- Sharing reasons: Starting with the project manager, each team member shares one reason from their list until all have been recorded.

- Plan strengthening: The project manager reviews the compiled list to identify ways to strengthen the plan.

For effective implementation:

- Create psychological safety for team members to share concerns without fear of appearing uncooperative or pessimistic.

- Ensure all team members participate, as diverse perspectives increase the likelihood of identifying risks.

- Document all identified risks and develop specific mitigation strategies.

- Revisit the premortem findings throughout the project lifecycle.

30.3 Benefits of premortems

Klein (2007) identifies several benefits:

- Early risk identification: The premortem helps teams identify potential problems at the outset when they can still be addressed.

- Counteracting overinvestment: The technique reduces the “damn-the-torpedoes” attitude often shown by people who are overinvested in a project. (The phrase “Damn the torpedoes” comes from a quote by Admiral David Farragut in the Battle of Mobile Bay: “Damn the torpedoes, full speed ahead!”)

- Valuing team intelligence: When team members describe weaknesses others haven’t mentioned, they feel valued for their experience and intelligence.

- Enhanced awareness: The exercise sensitises the team to recognise early warning signs once the project is underway.

30.4 Business examples

Klein (2007) provides the following examples.

In a military project involving computer algorithms for air-campaign planners, a previously silent team member revealed during the premortem that the algorithms wouldn’t run efficiently on field laptops. This led to the implementation of an existing shortcut that the developers had been reluctant to mention, ultimately contributing to the project’s success.

In another organisation, a premortem for a research project revealed insufficient time to prepare a business case before an upcoming corporate review. No one had mentioned the review during the 90-minute kickoff meeting. The project manager revised the plan to account for the review.