10 Heuristics and the bias-variance trade-off

While much of the heuristics and biases literature of Kahneman, Tversky and those who followed in their footsteps focuses on the errors that can be caused by the use of heuristics, there are also powerful reasons for their use.

One of the strongest arguments for the use of simple heuristics relates to what is called the bias-variance trade-off.

Suppose you are trying to make a prediction or develop an estimate based on historical data. There is a true underlying process that is generating the data. You plan to build a predictive model that should approximate the underlying process. You have a noisy data sample with which to develop it and you are trying to decide which predictors to include.

An example of this could be that you want to predict the level of drop out in a school. You have possible predictors such as attendance rates, family socio-economic status, the school’s average SAT score, and the degree of parental involvement in the child’s schooling. Which of those should you include in your model?

Bias is the degree to which there are erroneous assumptions in your model. The classic case of bias is when you have failed to include a relevant predictor. If you exclude relevant predictors, you introduce bias as your predictive model will not include relevant relations between the predictors and the target output you are trying to predict. On the school example above, to the extent any of these factors are linked to drop out rates, excluding them can bias your prediction.

However, inclusion of too many predictors can lead to what is called variance, which is an error that arises because of the sensitivity of the model to fluctuations in the data you use to develop the model. It ultimately involves giving too much weight to irrelevant or marginally relevant information.

For example, if you included the school colours in your model, it may appear to give you a better model due to noise. But as soon as you used it to make a new prediction, it would likely backfire.

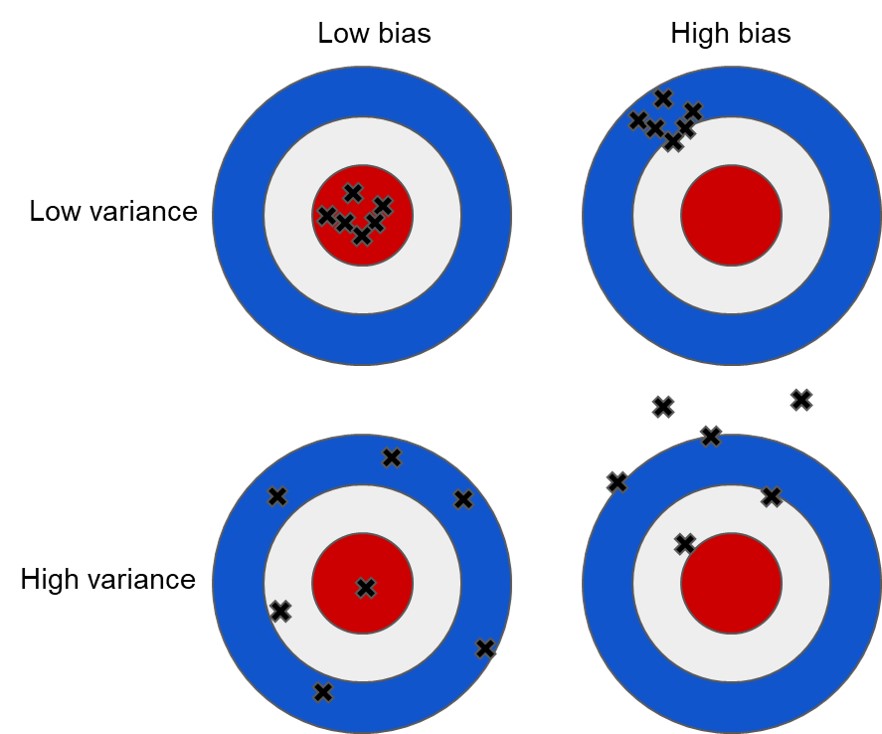

The following image gives on conception of bias and variance. An unbiased predictor will tend to centre on the target. A low variance predictor will tend to cluster. A low variance, low bias estimate is the best outcome.

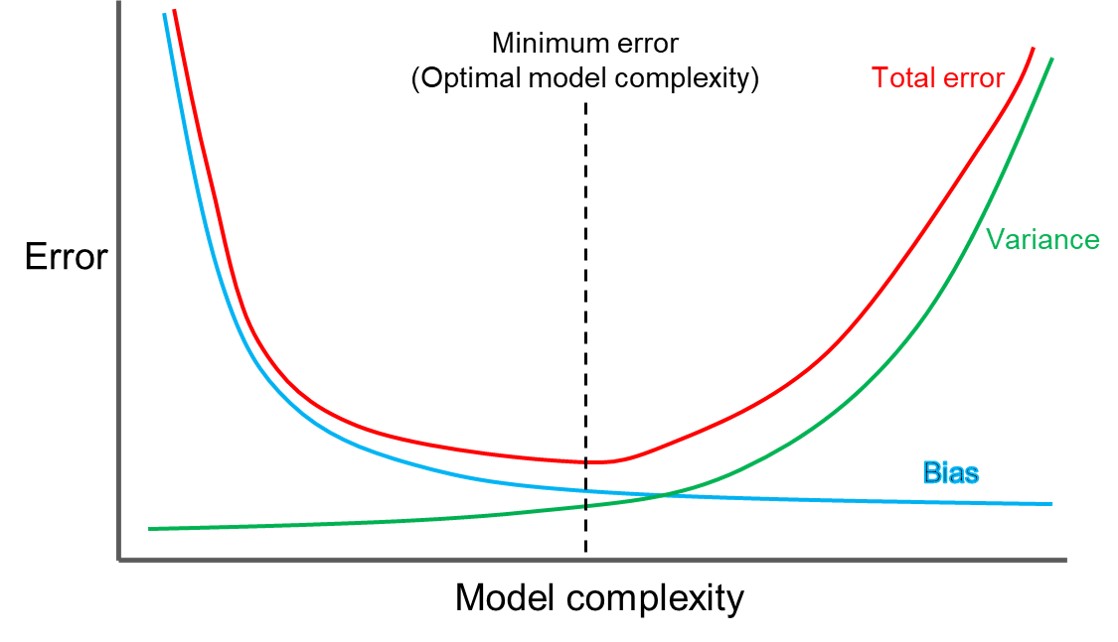

However, as the term bias-variance trade-off suggests, it is not that simple. There is a trade-off between the two. As model complexity increases, bias tends to decrease, but variance tends to go up. There is an optimal level of complexity.

The result of this bias-variance trade-off means that simple heuristics can sometimes be better than more complex decision making strategies. This is not just because they are tractable for the human mind, but also because they find a better bias-variance trade-off, which also leads to better performance. Despite our focus on how heuristics can backfire in corporate decision-making environments, there can be a power to them.

In fact, training in many MBA’s uses this. The case-study method effectively builds a repertoire of examples that managers can call on in decision making. It results in available examples in memory to call on when faced with a parallel situation. Relevant case studies are often selected based on their representativeness of the example at hand.

This is not to say the case-study method is not without flaws. But you can see the tractability of this approach, and potentially better outcomes, as compared to a first-principles examination of every business decision.

For further discussion of this topic, see Gigerenzer and Brighton (2009).