11 Hindsight

Knowing the outcome of an event makes it difficult to imagine what your judgment would have been had you not known the outcome. This often results in what is called “hindsight bias”. You knew it all along.

One explanation for why this occurs is that it is hard to think about a counterfactual that is now inconsistent with reality. You might have dreaded the holiday with your in-laws. But after a pleasant trip, with good company, nice weather and interesting sights, it is hard to ignore these new facts in stating your prior belief.

11.1 Stock picking

Louie (1999) asked people to decide whether they wished to purchase a stock. One group was asked whether they believed the stock would increase in value. Another group was told that the stock had increased or decreased in value before being asked about their belief at the time of their purchase decision.

People told that the stock increased were more likely to state that they believed that the stock price would increase than those who had not been told what had happened to the stock price. Similarly, those told that the stock decreased were more likely to state that they believed that the stock price would decrease.

11.2 College selection

Galotti (1995) asked high school students to state what criteria they would use to select their university and how important each criterion was. They were also asked how each university they were considering scored on each criterion.

When students were later at university, they were asked to recall the factors important to them and what they now considered important. Students did have some recall but tended to recall those factors that they now considered important.

11.3 Medical decision making

Hal Arkes (2013) summarises summarises Dawson et al. (1988) as follows:

A clinicopathologic conference (CPC) is a dramatic event at a hospital. A young physician, such as a resident, is given all of the documentation except the autopsy report that pertains to a deceased patient. After studying the material for a week or so, the physician presents the case to the assembled medical staff, going over the case and listing the differential diagnosis, which consists of the several possible diagnoses for this patient. Finally, the presenting physician announces the diagnosis that he or she thinks is the correct one. The presenter then sits down, sweating profusely, as the pathologist who did the autopsy takes the podium and announces the correct diagnosis. The cases are chosen because they are difficult, so the presenting physician’s hypothesis often is incorrect.

The CPC is supposed to be an educational experience. Its goal is to enlighten the audience members about diagnosing a particularly challenging case. However, after hearing the pathologist’s report, which contradicts the diagnosis made by the presenting physician, many audience members think, “Why aren’t we hiring residents as astute as my cohort of residents? This diagnosis was easy.” The audience members do not learn from the instructive case presented at the CPC. Instead, they criticize the presenter, because in hindsight, they think the case was relatively obvious.

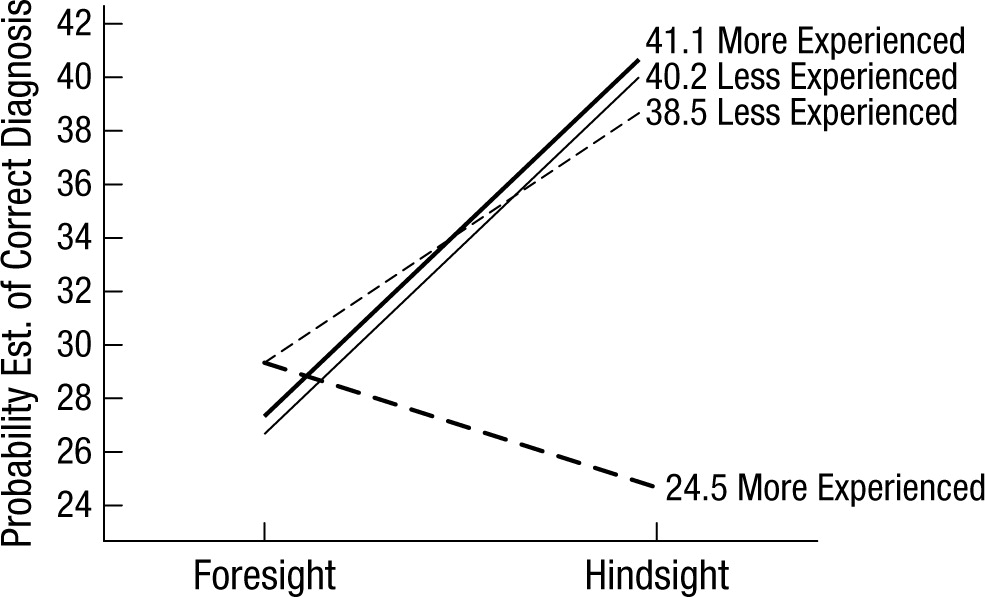

A CPC is fertile ground for the manifestation of the hindsight bias; after the correct diagnosis is disclosed, it seems as if it could easily have been discerned beforehand. Dawson et al. (1988) interrupted eight CPCs at two critical junctures. At each CPC, after the presenter listed the five possible diagnoses, the researchers asked half of the audience to assign a probability to each diagnosis (i.e., the likelihood that it was correct). These participants were in the foresight group, because they were asked to provide data before the correct diagnosis was revealed. These data were collected, the pathologist then revealed the true diagnosis, and the CPC was paused a second time for the other half of the audience to provide data. The researchers asked them to assign a probability to each of the five possibilities as if they had not just been informed of the right answer. These participants were in the hindsight group, because they were asked to provide data after the correct diagnosis was revealed. For each case, Dawson et al. asked two experts who had attended their domain-appropriate CPC to indicate, on a 10-cm line, what proportion of good clinicians would choose the correct diagnosis. The average of the two experts’ ratings was used to divide the eight CPCs into two quartets—one being the four more difficult cases and the other being the four less difficult ones. Dawson et al. divided the attendees into groups of less experienced and more experienced physicians on the basis of their training and seniority. As Figure 1 shows, in three of the four experience–diagnostic-difficulty groups, the hindsight participants estimated the correct answer to be more likely than the foresight group did. The difference averaged approximately 12 percentage points. Hindsight physicians mistakenly think that the case was easier than it really was (as evidenced by the predictions of the foresight subjects). The educational benefit of the CPC is consequently diminished, because the audience members think there is little or nothing to be learned, given that they retrospectively judge their diagnoses to have been relatively accurate.

Note that the most senior physicians diagnosing the most difficult cases escaped the hindsight bias. They realized that they were not likely to have made the correct diagnosis because a particular disease was so very rare or the presentation of the disease was so very abnormal.