7 Incentives in the workplace

In the previous part we considered how the principal can motivate their agent employee. That employee balances the marginal cost of their effort against the marginal benefit of the return to their effort.

However, experimental evidence shows that this picture of motivation is incomplete.

7.1 Example 1: choking

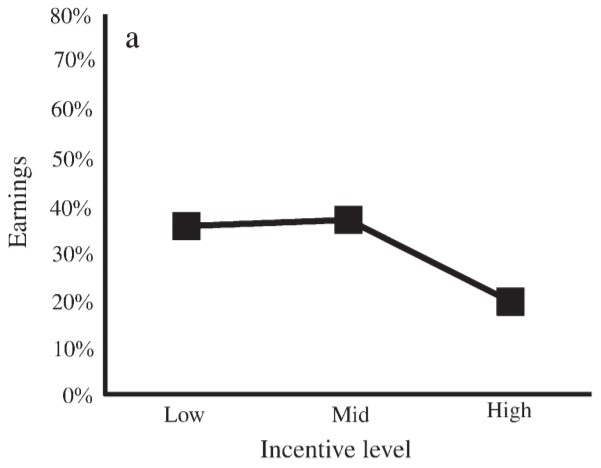

Ariely et al. (2009) provided experimental participants with financial incentives to undertake a series of tasks that required creativity, concentration, memory and problem solving skills. Some participants could earn a bonus equivalent to about one day’s pay. Others could earn a medium sized bonus equivalent to about two weeks pay. And a third group could earn a bonus worth around five months of their regular pay. (The experiment was done in rural India, so although the amounts were relatively large for the participants, they did not break the experimental budget.)

The result was that those who received the small or medium level bonus did not differ much from each other in performance. But those who had a large bonus on the line were the poorest performers. They choked under pressure.

7.3 Example 3: moral licensing

List and Momeni (2021) hired workers on Amazon’s online labour market platform, Amazon Mechanical Turk, and asked them to complete a short task for payment. They were then exposed to various corporate social responsibility messages.

List and Momeni found that the use of corporate social responsibility messaging increased cheating - both the number of workers who shirk their primary job duty and the level of the shirking. The share of cheating was highest when the corporate social responsibility message was framed as a prosocial act on behalf of workers.

This cheating is consistent with a higher level of “moral licensing”, whereby good behaviour in one domain liberates us to behave unethically in another while maintaining our self-image as a good and moral person.

For a popular discussion of the paper, Dubner (n.d.) discusses the paper with List.

7.4 Example 4: stakes

Much of the behavioural literature rests on experiments with low or no stakes. This is somewhat different from that experienced in corporate decision making, where stakes for both the individual and firm can be large.

There is a dearth of evidence of whether cognitive biases are directly reduced in a high-stakes corporate environment. More generally, there is a general lack of high-stakes experiments, with most direct examinations of incentives being an investigation into the difference between no and small stakes.

An exception is a recent paper by Enke et al. (2023), which examined the effect of high stakes on base rate neglect, anchoring, the failure of contingent thinking, and intuitive reasoning.

You have come across base rate neglect (in the context of the outside view) and anchoring earlier in this unit. The test of intuitive reasoning used the cognitive reflection test, with the following two questions:

A bat and a ball cost 110 KSh in total. The bat costs 100 KSh more than the ball. How much does the ball cost?(Intuitive answer is 10, correct answer is 5).

It takes 5 nurses 5 minutes to measure the blood pressure of 5 patients. How long would it take 10 nurses to measure the blood pressure of 10 patients?(Intuitive answer is 10, correct answer is 5).

(The currency is KSh as this work was done in Kenya.)

The test of contingent reasoning used the Wason selection task. One version used in the experiment runs as follows:

Suppose you have a friend who says he has a special deck of cards. His special deck of cards all have numbers (odd or even) on one side and colors (brown or green) on the other side. Suppose that the 4 cards from his deck are shown below. Your friend also claims that in his special deck of cards, even numbered cards are never brown on the other side. He says: “In my deck of cards, all of the cards with an even number on one side are green on the other.”

Unfortunately, your friend doesn’t always tell the truth, and your job is to figure out whether he is telling the truth or lying about his statement. From the cards below, turn over only those card(s) that can be helpful in determining whether your friend is telling the truth or lying. Do not turn over those cards that cannot help you in determining whether he is telling the truth or lying. Select the card(s) you want to turn over.

Which cards would you turn over?

(I am showing some of the particular tests here not because they are vital to the question of incentives, but rather that these tests appear again and again in the behavioural literature. It is worth becoming familiar with them.)

The headline of the experiment was that the large stakes did little to reduce the bias of the experimental participants, with the exception of the cognitive reflection test. Response times increased by around 40% with the large stakes, suggesting that the performance increase comes from a reduction in the reliance on intuitions.

As for why the experimental participants did not do better, the paper authors write that “some problems are sufficiently complex for people that the binding constraint is not low effort and reliance on intuitions but instead a lack of conceptual problem solving skills”

7.5 Example 5: increased base pay

Gneezy and List (2006) hired experimental participants to perform either data entry to computerise the holdings of a small library, or to undertake door-to-door fundraising. The advertisement for the position included the hourly rate they would be paid for the six hours of work, $12 and $10 per hour for the two roles respectively.

In both cases, a treatment group of employees was then told at the beginning of their employment that they would be paid a higher hourly rate of $20. The employees doing data entry boosted their effort in response markedly over the first 90 minutes, after which their effort became indistinguishable from those still paid $12 per hour. Similarly, the fundraisers who received the surprise pay increase raised much more money in the first few hours of the task, but after that were indistinguishable from those still paid $10 per hour.

7.6 Example 6: taxis on rainy days

Why can’t you find a taxi on a rainy day?

One possible explanation comes from Colin Camerer et al. (1997), who studied the labour supply of New York City taxi drivers.

The taxi drivers rent a cab for a 12-hour period for a fixed fee, plus petrol. Within the 12 hours, a driver can choose how long they keep the taxi out.

A taxi driver’s effective wage can vary for many reasons, such as weather, subway breakdowns, day of the week and conferences. When they are busier, they have a higher effective wage. That is, they earn more fares.

In two of the three samples they examined, Camerer et al. (1997) found that drivers drove less when their effective wages were higher. This was the case for inexperienced drivers in all three samples, and they drove significantly less than experienced drivers when wages were high.

This contrasts with the basic prediction of economic theory that supply increases with price. Supply curves slope upwards.

Camerer et al. argue that this result is because taxi drivers have a daily earnings target, beyond which they derive little additional utility. This leads them to work until they reach their target, which occurs more quickly on days with a higher wage.

They argued that the drivers engage in “narrow bracketing” when they make decisions each day, isolating them as single decisions (how much should I work today?) rather than thinking about them as a stream (how much should I work each day this week?)

Aversion to falling below the reference point is consistent with loss aversion, with a result below the reference point causing stronger feelings than a result a similar amount above the reference point.

There have been numerous follow-up studies of taxi drivers. The results of these studies have varied.

- Henry S. Farber (2005) studied New York cab drivers and found that the decision to stop work was primarily a function of how many hours had been worked up to that point in the day. He identified the difference between his and Camerer et al.’s result as being due to different empirical methods and measurement problems with the Camerer et al. data.

- H. S. Farber (2008) found that a labour supply model with reference-dependent targets better fits than a standard neoclassical model. However, there was substantial variation day-to-day in any given driver’s reference income level and most shifts ended before that reference income was reached.

- H. S. Farber (2015) used a much larger dataset on New York taxi driver behaviour and found that, as standard economic theory would predict, taxi drivers drive more when they can earn more. Farber also found that drivers did not earn more when it was raining.

- Finally, Martin (2017) examined taxi driver labour supply using the S-shaped reference dependence of prospect theory. That is, Martin used a model with the reflection effect, with risk-seeking behaviour in the loss domain and risk aversion in the gain domain. Martin found evidence that taxi driver behaviour was consistent with this full form of prospect theory. He differentiated from the other papers on the basis that they considered a narrower version of reference dependence focusing on loss aversion only.

7.7 Example 7: bonuses

Bareket-Bojmel et al. (2017) studied workers in a semi-conductor plant in Israel who were sent a message on day one of their four-day work stretch offering one of the following incentives if they met their target for the day:

- A $30 bonus

- A pizza voucher

- A thank you text message from the boss

- No message (the control group)

For people who were offered one of the three incentives, there was a boost to productivity on that day relative to the control: 4.9% for the cash group, 6.7% for the pizza group, and 6.6% for the thank you group.

The more interesting result was over the next three days. On day two, the group that had been incentivised with cash on day one had their productivity drop to 13.2% less than the control group. Absent the cash reward, they took their foot off the gas. On day three productivity was 6.2% worse. And on day four it was 2.9% worse. Over the four days, the productivity of the cash incentive group was 6.5% below that of the control. In contrast, the thank you group had no crash in productivity, with the pizza group somewhere in between. The cash reward on day one, but not the other days, had sent a signal that day one was the only day when production mattered. Or the cash reward displaced some other form of motivation.

Note: Some of Dan Ariely’s work has been called into question. You might want to take his experimental work with a grain of salt.

7.8 The incentives debate

What should you take from the above experiments? Are incentives ineffective?

Shaw and Gupta (2015) argue the following:

As with debates about whether the sun goes around the earth and whether there is climate change, the scientific evidence has spoken about financial incentives in work settings – they are effective, they improve performance quantity, they improve performance quality and they do not erode, but rather enhance the potency of, intrinsic motivation. It is time to put the issue of whether they work to rest; it is time to attend to issues of how and why they work.