21 Expert Political judgment

In Expert Political Judgment: How Good Is It? How Can We Know?, Tetlock (2005) reports on a project in which he asked a range of experts to predict future events. With the need to see how the forecasts panned out, the project ran for almost 20 years.

The basic methodology was to ask each participant to rate three possible outcomes for a political or economic event on a scale of 0 to 10 on how likely each outcome is (with, assuming some basic mathematical literacy, the sum allocated to the three options being 10). An example question might be whether a government will retain, lose or strengthen its position after the next election. Or whether GDP growth will be below 1.75 per cent, between 1.75 per cent and 3.25 per cent, or above 3.25 per cent.

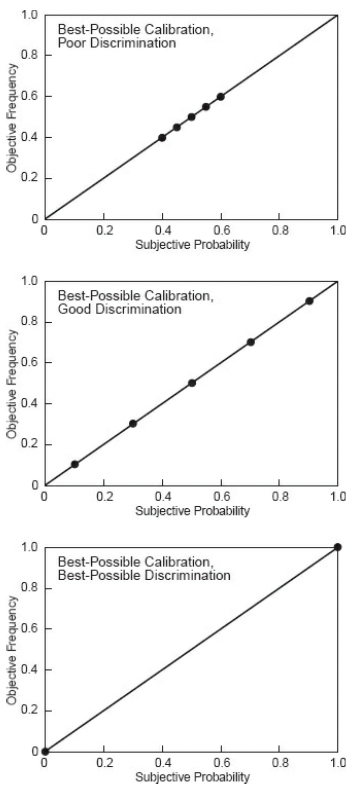

Once the results were in, Tetlock scored the participants on two dimensions - calibration and discrimination. To get a high calibration score, the frequency with which events are predicted needs to correspond with their actual frequency. For instance, events predicted to occur with a 10 per cent probability need to occur around 10 per cent of the time, and so on. Given experts made many judgments, these types of calculations could be made.

To score highly on discrimination, the participant needs to assign a score of 1.0 to things that happen and 0 to things that don’t. The closer to the ends of the scale for predictions, the higher the discrimination score. It is possible to be perfectly calibrated but a poor discriminator (fence sitter) through to a perfect discriminator (only using the extreme values correctly).

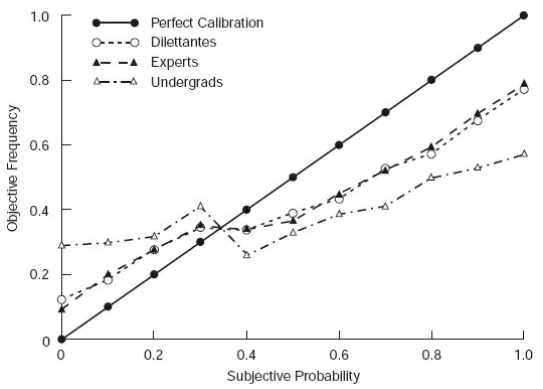

Tetlock’s analysis revealed that:

- Experts, who typically have a doctorate and average 12 years experience in their field, barely outperform equal probability of 33 per cent to each potential outcome.

- However, experts outperform unsophisticated forecasters (a role filled by Berkeley undergrads).

- The experts were not differentiated on a range of dimensions, such as years of experience or whether they are forecasting on their area of expertise. Subject matter expertise translates less into forecasting accuracy than confidence.

The one dimension where forecast accuracy was differentiated is on what Tetlock calls the fox-hedgehog continuum (borrowing from Isiah Berlin). Hedgehogs know one big thing and aggressively expand that idea into all domains, whereas foxes know many small things, are skeptical of grand ideas and stitch together diverse, sometimes conflicting information. Foxes are more willing to change their minds in response to the unexpected, more likely to remember past mistakes, and more likely to see the case for opposing outcomes. Foxes outperformed on both measures of calibration and discrimination.

What is it about foxes and hedgehogs that leads to differences in performance? Among other reasons, Tetlock identified the following:

- Foxes are better Bayesians in that they update their beliefs in response to new evidence and in proportion to the extremity of the odds they placed on possible outcomes. They weren’t perfect Bayesian’s however - when surprised by a result, Tetlock calculated that foxes moved around 59 per cent of the prescribed amount compared to 19 per cent for hedgehogs. In some of the exercises, hedgehogs moved in the opposite direction.

- Foxes were also less prone to hindsight effects. Many experts claimed that they assigned higher probabilities to outcomes that materialised than they did. As Tetlock notes, it is hard to say someone got it wrong if they think they got it right.